Dear Sovereign Redeemer and other friends,

Does it even need to be said that sermon preparation should start with the Bible work? By “Bible work” I mean the direct study of the sermon text itself, and the related cross-references, as opposed to what others say about the sermon text.

It is a great temptation to just skip to what Matthew Henry says (for instance), but a temptation which must be resisted. What quicker way can we imagine to quench the Spirit than an unhealthy – borderline idolatrous – reliance on men? Sermon preparation should begin with a quiet room and a Bible. The most important work in preparing a sound, expository sermon happens then.

Week in and week out, this describes my Bible work:

– Men’s Bible study. At Sovereign Redeemer, the men and boys who are willing and able meet for an hour on Monday morning to discuss the text that will be preached on the upcoming Sunday. Leading that discussion gets me into the text at the start of the week, and gives me exposure to the thoughts of a variety of men regarding the text. If there are particular interpretive challenges, I become aware of them right away.

– Searching out the best cross-references. The most important principle of Bible interpretation (or hermeneutic) is that Scripture interprets Scripture. Other related texts of Scripture are always the best commentary on the sermon text, and always the best source of explanation for difficulties in the sermon text. Always. So, after reading the sermon text slowly several times, and earnestly seeking the Lord for help, this is where I start. I look up every cross-reference from four sources (three study Bibles and Matthew Poole) one by one, looking at each in context and considering the bearing of each on the sermon text. My guess is that 75% of the finished sermon comes from this exercise. I cannot stress enough how invaluable this step is.

– Comparing translations. Years ago, at an expository preaching conference, Dr. Andy Davis gave a message in which he said that if a preacher hasn’t studied the original languages (Hebrew in the Old Testament, Greek in the New), the next best thing is a comparison of reliable English translations. At points of translational agreement, the English word uniformly selected by the translators is a close equivalent to the word in the original language. At points of translational variation, the underlying Hebrew or Greek word is worth researching. Having never studied Hebrew or Greek, this has been very valuable advice for me. I use Bible Gateway, an online tool which allows for side-by-side comparison of selected translations. Here is the link that I use, which compares NKJV, KJV, NASB, ESV, and NIV.

– Looking at the original language. For very prominent, important words in the text, and for places where significant translational variation exists, I look at the Hebrew or Greek. I use the online tool Blue Letter Bible. By entering the text, then selecting the verse, then selecting the Strong’s number for the word in question, a multitude of information is made available. Not only is information from the Lexicon very valuable, but the other places where the same word is used is displayed. Looking at the other usages of the same word is often pure gold.

– Creating a basic outline. At this point I make a first attempt at creating a high level structure for the sermon. Having done the Bible work, I should have begun forming a view of how the text could or should be preached, and this forces me to begin articulating that. This first outline usually represents no more than fifteen minutes of scribbling on a legal pad, but it moves my thinking from what I am learning to how I might communicate what I am learning, which are vastly different things.

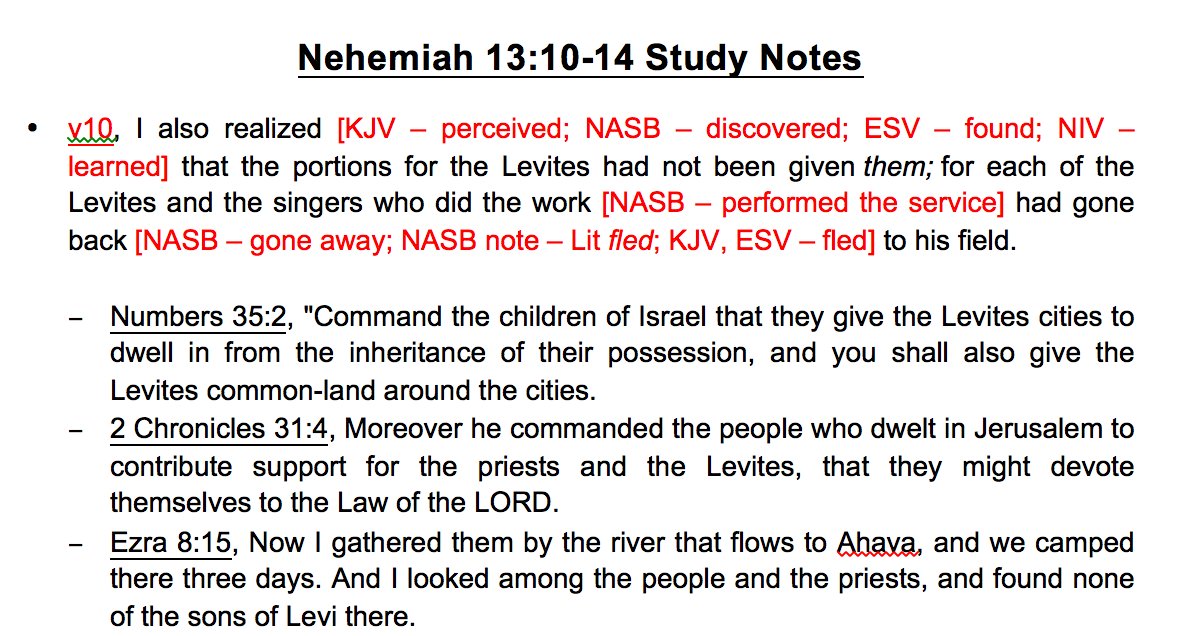

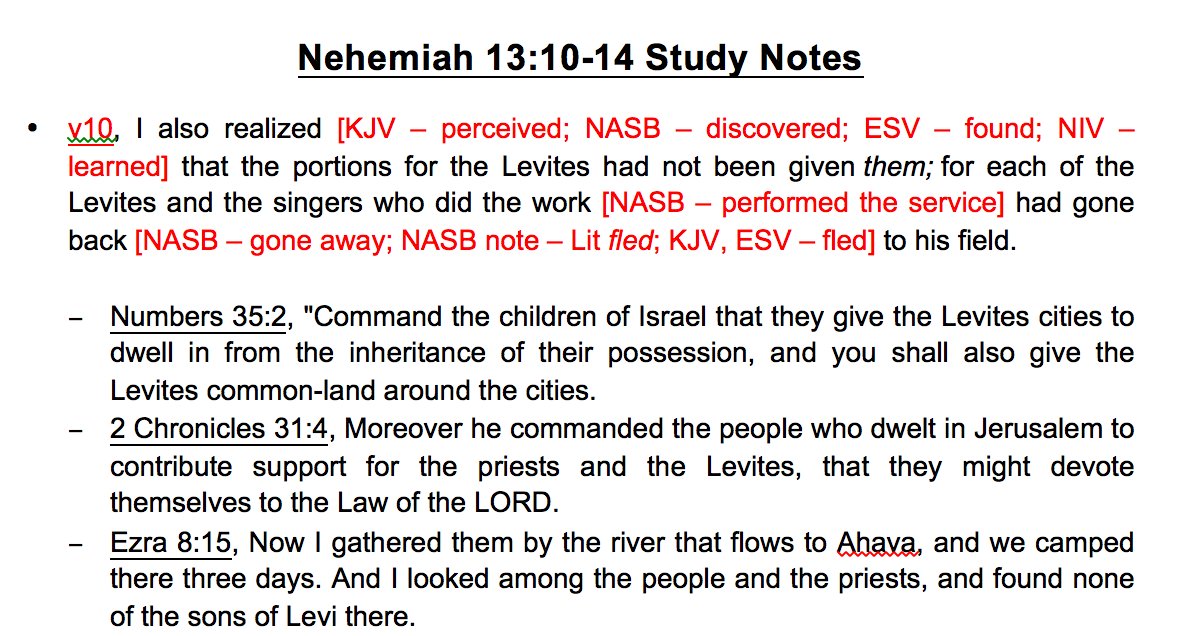

When all of this is complete, I have the beginnings of my study file, which I continue to populate throughout the week. For this series of posts, I am going to use a recent sermon that I preached on Nehemiah 13:10-14 titled “Forsaking the House of God” as an example. Here is what my study file looked like after having completed the Bible work I have been describing:

If you want to see the whole file, you can access it here.

A few things to point out:

- I start by separating the verses of the sermon text, so that each verse of the sermon text begins a section of the material related to that verse.

- Within the verse of the sermon text, I note any translational variations and/or facts about the original language in brackets and red text.

- The cross-references are below each verse of the sermon text.

- On an average week, the Bible work requires 3-4 hours.

- As the week progresses and I continue to study, new material goes below the cross-references.

In my next post, I will discuss the outside helps – the study Bibles and commentaries – that I utilize to help me better understand the sermon text.

* As a side note, fantastic Bible study tools exist that are not even referenced in this post. I have not invested in these yet, but I have no doubt of their tremendous value. If you are interested, here is a detailed review of two of them.